The recent Fraser Institute survey of mining globally has seen South Africa drop to 74th place out of 104 mining jurisdictions, down from last year’s 66 . We now rank behind the likes of the Democratic of Congo and Zambia, which has regained its place in the top 50. This is a pretty pass for a country with such rich mineral resources, and one that was once a global leader in mining.

It is common cause that one of the primary drivers of South Africa’s unattractiveness as mining destination is the regulatory uncertainty that has prevailed since 2012, when the current Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA) was amended. The robust instrumentation of our constitutional democracy and rigorous scrutiny to which the Bill was subjected resulted in it being passed by the National Assembly late in 2016. It is currently before the National Council of Provinces.

Regulatory certainty critical

The need to give both the minerals/mining and petroleum/hydrocarbons industries regulatory certainty has now become critical. Certainty is the only thing that will reverse the current investment freeze which is currently impeding progress in both industries. The urgency is real, given the sustained lacklustre performance of the South African economy. Mining remains a bedrock of the economy, a major contributor to GDP and a significant provider of employment. Nursing this once vibrant industry back to health is of critical importance. Doing so will require certainty and the ability of the actors to reinvent an industry with enhanced efficiencies supported by greater reliance on technology and modernisation.

By contrast, our petroleum sector is embryonic and offers has significant potential, in particular the promise of the development of a natural gas economy. We know that large, commercially viable gas fields exist off the coasts of Mozambique and Madagascar, and the protagonist for “following the rift” believe that that mineral-rich South Africa might also have similar reserves. We already know that significant shale gas deposits exist in the Karoo though, of course, whether they are safe to exploit remains highly controversial. This emerging industry will only grow if sufficient capital is committed to exploration, and that will not occur until investors know what the regulatory environment is.

The National Development Plan recognises the potential importance of gas in creating an economy that uplifts the people of this country.

Based on conversations with clients, it seems that the current provisions in the amended act are acceptable. These include a 20 percent carried interest for the automatic state interest in discoveries, which interest can be increased at a market-related rate. This setting aside of a state interest in petroleum discoveries has become commonplace, and 20 percent is considered conservative.

Differences between mining and petroleum sectors undermines legislation

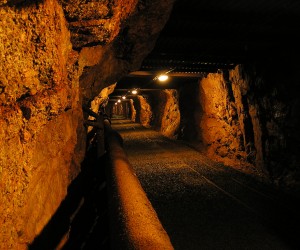

But it is the profound difference between these two industry sectors that undermines this legislation. Mining in South Africa is a mature industry with an established infrastructure in all senses of the word, and is well known to the global investment community. It also has a dark history, and the need to control the country’s abundant mineral resources arguably shaped the history of the country, particularly since 1948. In a real sense, the repressive power structures and damaged social fabric that still characterise South Africa are, in many respects, a product of the mining industry’s history.

In other words—and nobody in the industry can deny this basic premise—mining needs far-reaching transformation. Agreeing on the details of how best to achieve this will continue to be tricky, as evidenced by the ongoing disagreement about and resistance to the proposed terms of the Mining Charter.

By contrast, the petroleum/hydrocarbon industry barely exists. It thus has no history to rewrite; its requirement is a sensible, progressive regulatory framework that will stimulate massive investment to enable growth, sustainable access to lower cost cleaner energy and, ultimately, job and wealth creation.

Thus, once we have returned certainty to the minerals and petroleum industries, and hopefully reignited investor interest, we do need to consider whether it makes sense to regulate these two industries separately, in line with their different needs. Care would need to be taken to do so in a way that does not reintroduce uncertainty into the market, but actually reinforces that certainty.