As the country emerges from a volatile five-month long strike in the platinum mining sector, the Wits Art Museum (WAM) opens an extraordinary exhibition focusing on migrant workers in South Africa. Migrant labour is fundamental to the making of modern South Africa and the exhibition tells the stories of these men.

Ngezinyawo – Migrant Journeys is rich and diverse, and spans many years of collective heritage. Items on display include contemporary artwork, archival documents, photographs, films, music, artefacts from ethnographic collections, and interviews. It glaringly highlights that 20 years into democracy, there are still numerous, unresolved problems associated with the system of migrant labour.

The elaborate art, dress, dance, music and song that migrants crafted to assert and express their humanity feature prominently. Life was and continues to be difficult for migrant workers. Performance and song played a vital role in passing on oral histories, for social commentary and artistic expression. These creative outputs show an ability to survive with dignity despite the daily hardships they faced.

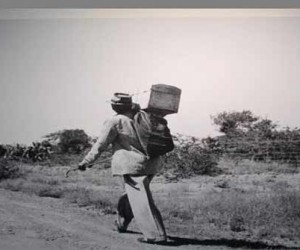

Like the migrants, visitors to the exhibition participate in a physical journey through the museum. They walk the road alongside early migrants to the cities, who mainly sought work on the mines. Overcoming hostility, harsh living conditions, violence, dispossession and loss are the recurrent themes at the exhibition – yet there are also themes of resilience and creativity.

The glitter of gold

South African society changed greatly when gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand in 1886. This discovery was central to South Africa's industrial development and to the politics of segregation. Here, on the goldfields of the Rand, the lives of many people intersected. Within a decade, Johannesburg had developed into the largest city in South Africa, populated by tens of thousands. Prospectors, labourers, fortune hunters, shop keepers and immigrants from all over the world flocked to the city. Residential areas were hastily constructed and in the poorer sections slums developed.

As the mines went deeper underground, the demand for cheap labour intensified. The Chamber of Mines asked the government to provide a cheap labour supply. Over time, the state introduced a number of measures to force more black men to work in the mines. These included introducing taxes such as the hut tax and the poll tax – they had to leave their land to work in the city to earn money to pay the taxes.

For its part, the Chamber of Mines preferred to use migrant labour because they could be paid very low wages. The industry justified the low wages by claiming that the migrants' families earned an additional income in the reserves. Because migrants were supposedly only part-time workers, the mine owners did not have to provide them with any kind of social security. Mine owners also preferred migrant labour because the workers could be controlled more easily. The men had to sign employment contracts. If they broke their contracts by deserting, which many did, they were arrested and got a criminal record. The migrants were also housed in closed compounds, or hostels, which were tightly controlled.

Conditions on the mines were very bad in the early decades. Workers often laboured 14 hours a day. Deaths from major accidents, pneumonia, tuberculosis, silicosis and malnutrition were extremely high.

Tracing the journey

Tracing the journey from rural areas to the city, the interactive exhibition includes personal objects such as hut tax receipts and a stamped passbook. There are envelopes decorated by self-taught artist Tito Zungu. Using pencil, ballpoint pens and coloured pens, the envelopes were decorated with images of boats, aeroplanes and transistor radios. Moving between time and space, these envelopes made the journey from work to home, linking the migrants' different worlds. They spent long periods of time away from their families and letter writing was the only means of communication.

Personal objects such as walking sticks, snuff bags and pipes that the workers carried with them were powerful reminders of the homes and families they left behind. These objects can be thought of as symbols of the personal journey that they made.

Single-sex compounds with concrete bunk beds and cold, bare walls were constructed to house migrant mine workers. Some of these mining compounds, or hostels, are still in use today, although the city of Johannesburg is renovating them and turning them into family units. Photographs and other remarkable objects on display provide insight into the living conditions and hardships encountered in hostels. But there are also extraordinarily creative everyday objects, music and performances that transcended the daily struggle.