When a bank is in trouble, as we saw in 2008, it can cause problems for the wider market and economy. In fact, massive efforts have been made since 2008 to reduce the risk large banks pose to the global economy. For one thing, banks have been forced to scale back risky trading and increase capital buffers so that taxpayers not again have to bail them out. Big multinational banks have paid around US$200 billion in fines for misdeeds leading up to the 2008 crisis (and thereafter).

The best way to improve capital buffers is to retain profit, but the environment for making profit in Europe has been extremely difficult. Banks still have to make a large provision for bad loans after two recessions in the past eight years. New loan growth is crawling along at around one percent per year (after several years of falling) while ultra-low interest rates across all maturities of the yield curve mean banks struggle to make money by borrowing short-term and lending for long terms. Banks might still be forced to raise capital by issuing shares and diluting existing shareholders.

The bond yields of peripheral countries – Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal – have risen again but remain well below the levels last seen during the 2012 ‘PIIGS’ crisis when fears over negative feedback loop between weak banks and weak governments gripped markets (banks tend to hold a lot of government debt as assets on their balance sheets).

Is this a replay of the 2008 bank crisis? Banks have spent the last few years shrinking and de-gearing, while typical bank crises follow periods of rapid debt-fuelled growth. Importantly, the European Central Bank is now fully active in its role as lender of last resort, something that was missing in 2012. But markets are questioning whether central banks – willing as they are – are able to do more.

Negative rates spreading

The Bank of Japan took the unprecedented step of cutting its main policy rate to -0.1% recently, but the market’s reaction did not go according to script. The yen has now strengthened to Y113 and the Nikkei has sold off sharply. Negative interest rates are very much a monetary experiment and it is too soon to tell whether the intended benefits will materialise, while the unintended consequences are still unknown. Some US$6 trillion bonds are trading at negative yields, including Japan’s 10-year bonds.

As recently as 2014, it was unheard of. While it is fairly certain that central banks will continue to fight the good fight, we might be reaching the limits of what they can achieve. Sweden’s Riksbank, however, seems to believe that the benefit from sub-zero rates outweigh any costs. They cut deeper into negative territory last week surprising markets.

Against this backdrop, the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) December rate hike is starting to look like an error and the next move will be crucial. The US 10-year bond yield dipped to 1.5%, while two-year rates have fallen from one percent at the start of the year to 0.66%. The market is certainly disagreeing with the Fed’s December outlook of four rate hikes by end 2016. In testimony before Congress, Fed Chair Janet Yellen reiterated that rate hikes are not on a “preset” course, meaning that the Fed will only hike rates if conditions warrant it. She also noted that the Fed was concerned that global developments could weigh on the US economy.

With US rate expectations being tempered, the US dollar has softened, taking pressure off the rand. Given that most central banks are still cutting rates, South African real interest rates must appear very attractive, especially since the rand is undervalued on most metrics.

Global growth disappointing, but still positive

The underlying issue is simply that global growth is disappointing (but still positive). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has cut its forecast for global growth nine times since 2014. It is natural that markets will adjust their expectations downward and also that they overreact, selling off first and asking questions later.

Many investors are forced by losses in one area (such as oil) to sell unrelated assets, irrespective of fundamentals. Long-term investors are able to look through the current fears on the market.

Chart 1: European banks compared to global equities

**********INSERT IMAGE 002**********

Source: Datastream

Mining problems

The recent annual Mining Indaba held in Cape Town is one of the largest gathering of mining executives and investors globally. The key theme this year, understandably, was the dismal state of the mining industry. Commodity prices have tumbled and the painful process of restructuring is underway. As soon as mining companies cut production in response to lower prices, the oversupply can be absorbed and prices can rise again. Apparently, we are only at the beginning of this process. As they say, when in a hole, the first step is to stop digging.

Local constraints

Apart from tumbling commodity prices, local mining companies face high and rising input costs, squeezing margins. According to the Chamber of Mines, electricity now makes up 17% of running costs of a typical mine after tariffs rose by almost 20% per year since 2008. Of the other main inputs, diesel prices, wages and reinforcing steel prices all increased by more than 10% per year. Also weighing on the local industry is regulatory uncertainty, and of course, a volatile labour relations environment. Mining production declined marginally by 0.3% in December, but was up by 1.5% between November and December.

Importantly, the quarter-on-quarter growth rate was positive, only barely though. Therefore, mining should make a positive contribution to fourth quarter Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at a time when the economy needs every single basis point of growth it can find. Mining contributes around 8% directly to GDP, but also supports other industries – manufacturing, construction and services. Taking a somewhat longer-term view, the StatsSA Mining Index is only slightly higher than it was in 2010. Mining output has barely grown over the past five years.

On a year-on-year basis, there were big declines in iron ore (-17%), copper (-15%) and diamonds (-8.5%). These were mostly offset by a 19% increase in output of platinum-group metals. The most important minerals are coal (26% of production), gold (21%), platinum-group metals (19%), and iron ore (15%).

Gold regaining its shine

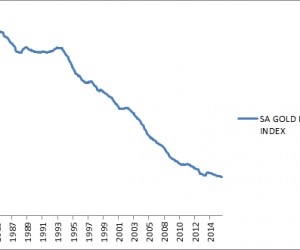

Although gold production fell in December (-4.9% year-on-year), the outlook for this sector is positive for a change. As a result of turmoil on markets and the introduction of negative interest rates, the US dollar price of gold has increased by 17% this year.

Since a gold bar does not pay any interest or dividend, the prospect of increasing US interest rates (and a rising US dollar) placed pressure on the gold price until the end of last year. However, negative rates are now spreading. Rather than paying a government for the privilege of lending them money, one might as well buy some gold. Gold is therefore certainly not rallying on its misplaced status as an inflation hedge – since inflation is the one commodity the world is desperately short of.

At around US$1200/oz the gold price is still well below the peak of US$1800/oz achieved in late 2011. In rand terms, however, the price of gold rocketed over the past few months. The rand price of gold hit R15,400/oz in late 2012 and drifted sideways until July last year. It is now trading at R19,600/oz. Whether the higher rand price of gold will boost output is debatable. The decline in gold output has been evident for many years, 130 years of mining has depleted most of the ore, forcing ever deeper mine shafts.

It will, however, boost gold mining profitability (which in turn will help increase corporate tax collection at a time when the government is desperate for more revenue). The shares of gold mining companies reflect this: the JSE Gold Mining Index is up almost 80% this year, well ahead of the General Mining Index (7%) and the broader Resource Index (1.2%). The Platinum Index rallied 30% so far this year due to the combination of slightly higher US dollar platinum price ($962) and the weak rand.

Chart 2: The long decline of SA gold output 1980 to 2015

**********INSERT IMAGE 003**********

The fact that the mining and resources indices are positive at all is encouraging after the sharp declines of the past few years, but there is still a long way to go to make up these losses.

Izak Odendaal, Investment Analyst at Old Mutual Wealth

PULL QUOTE: “Commodity prices have tumbled and the painful process of restructuring is underway”

PULL QUOTE: “Although gold production fell in December (-4.9% year-on-year), the outlook for this sector is positive for a change”